The COVID-19 pandemic has had substantial and often counter intuitive impacts on the BC economy and housing market. As we hopefully put the worst of the pandemic behind us and look ahead to a post-pandemic world, there remains significant uncertainty about what exactly that world is going to look like. In this Market Intelligence, we look at five questions for the post-pandemic BC housing market:

The COVID-19 pandemic has had substantial and often counter intuitive impacts on the BC economy and housing market. As we hopefully put the worst of the pandemic behind us and look ahead to a post-pandemic world, there remains significant uncertainty about what exactly that world is going to look like. In this Market Intelligence, we look at five questions for the post-pandemic BC housing market:• How long until markets return to balance?

• Will demand for extra space persist post-pandemic?

• Is remote working here to stay?

• When might immigration normalize and what does that mean for housing?

• Will high inflation lead to a sharp rise in mortgage rates?

1. How long until markets return to balance?

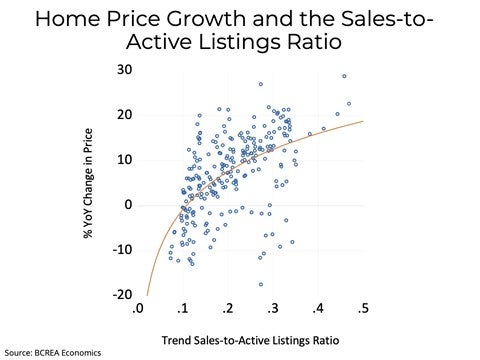

There is perhaps nothing closer to an iron law in the housing market than the relationship

between the sales-to-active listings ratio and home prices. When the ratio is very high, as it

is now, prices are going

to rise. This is shown in the monthly scatter plot relating changes in average price to the sales-to-active listings ratio trend over the past 20 years. The sales-to-active listings ratio can be high due to strong sales, low active listings or, as is the case now, a combination of both. However, low active listings have been a major contributor to rising prices for the past several years.

to rise. This is shown in the monthly scatter plot relating changes in average price to the sales-to-active listings ratio trend over the past 20 years. The sales-to-active listings ratio can be high due to strong sales, low active listings or, as is the case now, a combination of both. However, low active listings have been a major contributor to rising prices for the past several years. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, housing markets all over the province had been operating at very low levels of inventory. Once the pandemic hit and potential sellers pulled listings or held off listing their homes for fear of viral spread, re-sale listings fell to crisis levels.

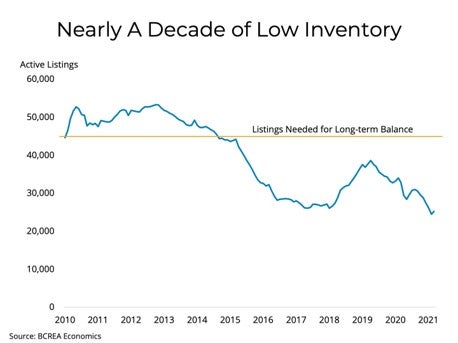

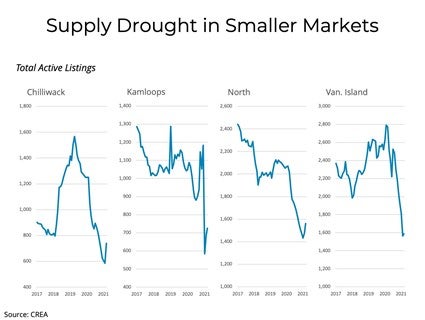

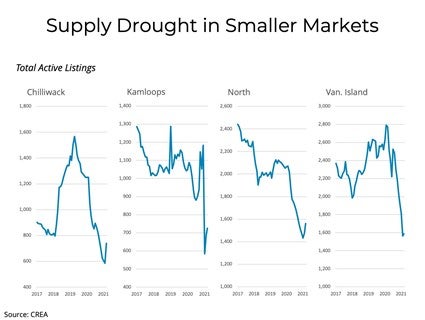

After a year of very strong price gains and vaccinations ramping up, new listings have accelerated, but inventories are a very long way from the healthy levels needed to reign in price growth. At a long-run average level of home sales, the province needs about 45,000 active listings to keep prices growing in line with inflation. At just 22,000 currently, there is a large deficit of listings that needs to be made up for. In fact, there is a significant listings gap in every market in the province, with some markets much more severe than others.

What is needed to bring markets back into balance? Some combination of continued strong listings activity and a moderation of sales from their current record pace to something more historically normal. While sales are showing some signs of cooling off, a strong economy, re-opening borders, massive household savings and very low mortgage rates will keep demand above normal for the next year. On the supply side, new listings in Metro Vancouver have trended higher and should continue to get a boost as the province surpasses key vaccination thresholds. However, smaller markets around the province, where inventories are lowest, have not seen the same recovery in new listings activity.

What is needed to bring markets back into balance? Some combination of continued strong listings activity and a moderation of sales from their current record pace to something more historically normal. While sales are showing some signs of cooling off, a strong economy, re-opening borders, massive household savings and very low mortgage rates will keep demand above normal for the next year. On the supply side, new listings in Metro Vancouver have trended higher and should continue to get a boost as the province surpasses key vaccination thresholds. However, smaller markets around the province, where inventories are lowest, have not seen the same recovery in new listings activity. With strong sales prevailing over the next two years, our current projections suggest that balanced markets are still quite a ways off.

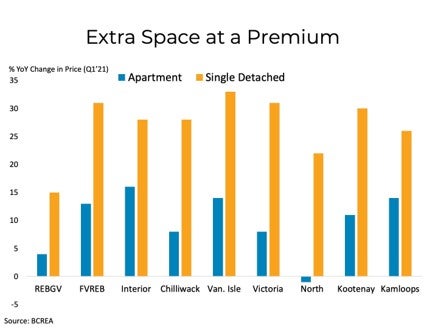

2. Will elevated demand for extra space persist post-pandemic?

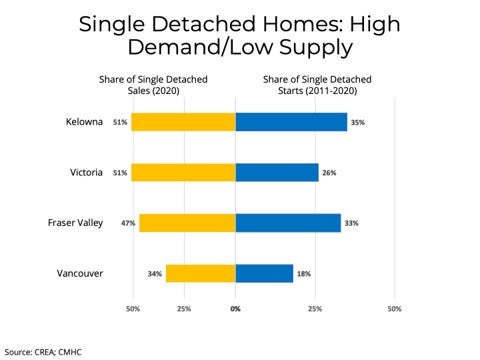

One of the most significant trends arising from the pandemic is a shift in buyer preferences toward acquiring extra space. Homes have suddenly become a workplace, a school, an entertainment centre and a refuge, and buyers have been willing to pay a significant premium to accommodate those new and diverse needs. That demand for space has run headlong into a part of the market that is scarce on supply after a decade in which most development was focused on multifamily housing. As a result, sales and prices of single-detached homes, especially in areas outside of major metropolitan markets, have skyrocketed. A key question for the post-pandemic market is whether this trend will persist. Much of the answer is based more on psychology than economics. There is research showing that the effects of the pandemic may be longlasting. For instance, in a small study of individuals who were quarantined during the Toronto SARS outbreak, participants described behavioral changes that lasted years following the end of the outbreak.

One of the most significant trends arising from the pandemic is a shift in buyer preferences toward acquiring extra space. Homes have suddenly become a workplace, a school, an entertainment centre and a refuge, and buyers have been willing to pay a significant premium to accommodate those new and diverse needs. That demand for space has run headlong into a part of the market that is scarce on supply after a decade in which most development was focused on multifamily housing. As a result, sales and prices of single-detached homes, especially in areas outside of major metropolitan markets, have skyrocketed. A key question for the post-pandemic market is whether this trend will persist. Much of the answer is based more on psychology than economics. There is research showing that the effects of the pandemic may be longlasting. For instance, in a small study of individuals who were quarantined during the Toronto SARS outbreak, participants described behavioral changes that lasted years following the end of the outbreak.

This could mean that the pandemic will have a lasting impact on the preferences of buyers and a continued desire for extra space and the safety, utility and flexibility that space provides. If so, that will continue to drive high demand for single-detached homes, and meeting that demand with sufficient supply, especially in larger cities, will be exceedingly difficult. As a result, high prices for single-family homes in all provincial markets may be quite persistent. However, that depends to some degree on our third question for the post-pandemic market concerning remote work.

3. Is remote working here to stay?

One substantial shift in our way of life due to the pandemic is how and where we work. About one-third of the Canadian workforce worked most of their hours from home in the first months of 2021, up from just 4 per cent in 2016. A question that remains is whether this change is a permanent shift or whether the “new normal” for office work will look a lot like the “old normal.” Statistics Canada identified three conditions for remote work to persist in the postpandemic world. First, employees must be as productive at home as they were in the office. Second, employees must have a strong preference for remote work. Third, employers must be willing to accommodate employees’ demand for remote work.

One substantial shift in our way of life due to the pandemic is how and where we work. About one-third of the Canadian workforce worked most of their hours from home in the first months of 2021, up from just 4 per cent in 2016. A question that remains is whether this change is a permanent shift or whether the “new normal” for office work will look a lot like the “old normal.” Statistics Canada identified three conditions for remote work to persist in the postpandemic world. First, employees must be as productive at home as they were in the office. Second, employees must have a strong preference for remote work. Third, employers must be willing to accommodate employees’ demand for remote work.  On the first condition, 90 per cent of workers reported being at least as productive at home as they were in the office, with a substantial portion of workers reporting greater productivity while working from home.

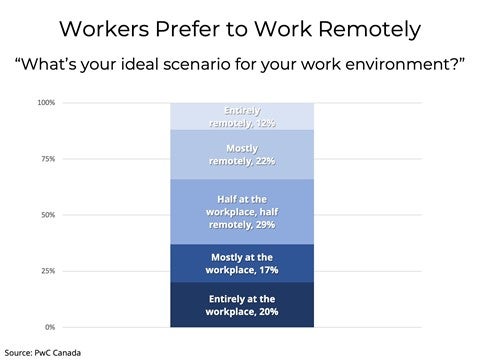

On the first condition, 90 per cent of workers reported being at least as productive at home as they were in the office, with a substantial portion of workers reporting greater productivity while working from home. Secondly, most workers have expressed a preference for working from home. In a recent PwC Canada survey, 63 per cent of Canadian employees expressed a desire to work remotely at least half of the time.

While workers report strong productivity and a desire to work remotely, it is yet unclear if the third condition is satisfied. It may be a challenge for employers to satisfy the diverse needs of a remote workforce, remote-work productivity could dip in a post-pandemic world with many more options for distraction, and there may be something important lost for both employers and employees in a work environment without casual, unscheduled faceto-face interaction.

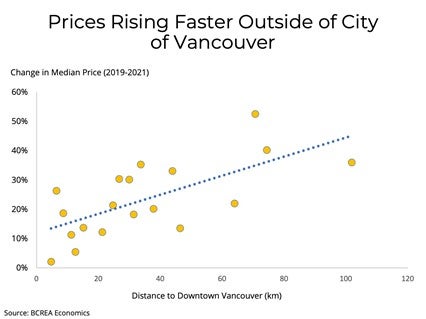

The persistence of remote work has major implications for the BC housing market, especially in markets more removed from major metropolitan areas where office work is concentrated. Since the onset of the pandemic, markets outside of metro areas have seen surging demand for homes. The housing stock in those smaller markets was not able to absorb the sudden increase in demand, leading to rapidly rising home prices and a severely depleted inventory of homes for sale.

If remote work is here to stay, smaller markets may continue to see not only higher than normal levels of demand, but demand from buyers whose incomes may not be reflective of historical norms for smaller markets. If that is the case, increasing the supply of homes in those markets is going to be vitally important to ensure those markets can remain affordable.

4. When might immigration normalize and what does that mean for housing?

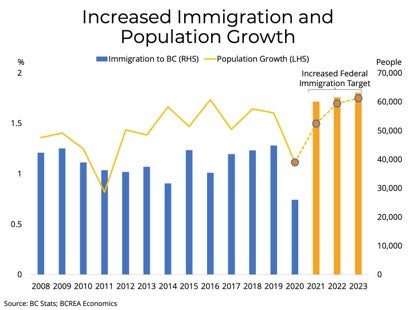

The impact of the pandemic on BC population growth was most prominently characterized by falling immigration numbers as borders closed. BC’s population ultimately expanded 1.1 per cent in 2020, its slowest rate of growth since 2011, and registered its lowest immigration since 1989.

The impact of the pandemic on BC population growth was most prominently characterized by falling immigration numbers as borders closed. BC’s population ultimately expanded 1.1 per cent in 2020, its slowest rate of growth since 2011, and registered its lowest immigration since 1989. While there was more than enough demand in the BC housing market to withstand a year of low population growth, demand is all about population growth and demographics in the long term. In BC, the most important contributor to population growth has been international migration (immigration). In the last five years, immigration has made up two-thirds of BC’s annual population growth.

Given the federal government’s increased immigration targets, we fully expect immigration to BC to not only normalize but increase substantially. The unanswered question in the post-pandemic environment is when will it be safe to resume open borders?

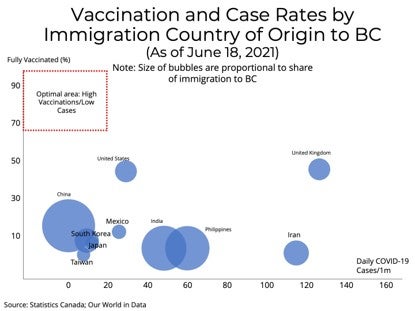

Looking at the main countries of origin for immigration to BC in recent years, many of those countries are not as far along in getting the pandemic under control as Canada. This suggests we may not see a full return to normal on immigration flows until perhaps next year when vaccination and case rates have improved in those countries. A more immediate impact, especially for condo markets near BC’s large universities, is the return to in-class learning and the return of international students.

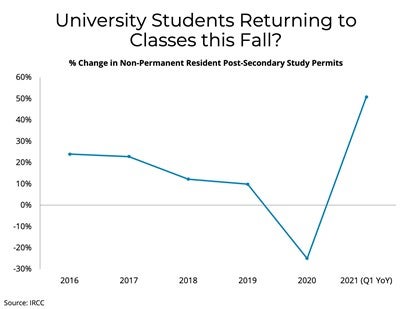

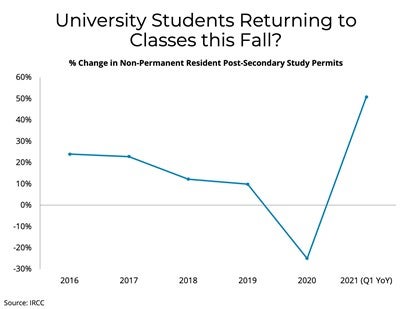

With vaccinations in BC rapidly approaching important herd immunity thresholds, most BC colleges and universities are planning to resume full-time, in-class learning this fall.

The lack of international students, and in-class learning in general, was acutely felt in the rental markets near large BC universities as low rental demand contributed to a decline in rents in both Vancouver and Victoria. BC is already seeing an increase in post-secondary study permits for non-permanent residents in the first quarter of 2021 and those numbers should continue to increase with plans for students to return to in-person classes this fall. As a result, the condo market should see a significant jump in demand even before a more permanent increase in immigration takes hold next year.

5. Will high inflation lead to a sharp rise in mortgage rates?

The five-year fixed mortgage rate has been on a downward trend for close to two decades as economic, demographic, and global financial factors have conspired to keep borrowing costs low.

In 2018, it appeared that Canadian mortgage rates were finally rising after a prolonged period of historically low levels. The Bank of Canada began raising its overnight policy rate in the summer of 2017, though that tightening cycle was short-circuited by slowing economic growth. The Bank’s policy rate ultimately plateaued at 1.75 per cent, at the low end of what the Bank considers to be its long-run “neutral” range of 1.75-2.75 per cent. The five-year fixed mortgage rate ultimately peaked short of 4 per cent at an average of 3.7 per cent in the early month of 2019 before sliding lower and finally cratering to new record lows when the COVID-19 pandemic struck and the Bank of Canada injected billions of dollars of liquidity into bond markets.

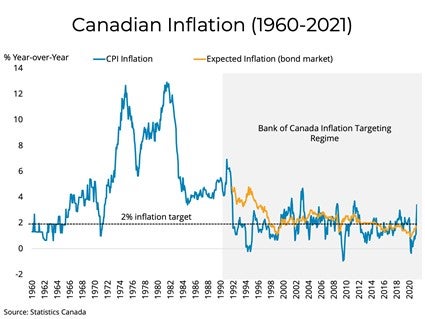

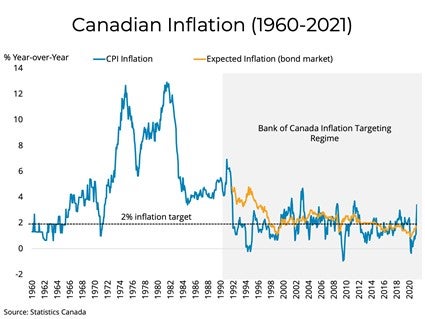

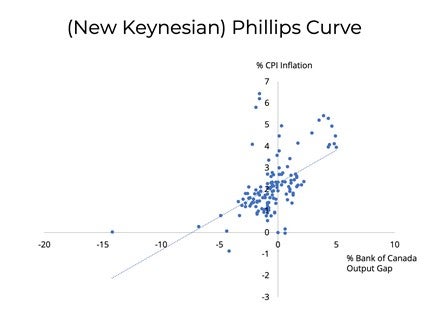

Because the Bank of Canada is mandated to target 2 per cent inflation, when we ask about the outlook for interest rates, we are really asking about the outlook for inflation.

The outlook for inflation is highly uncertain and is currently one of the most hotly debated topics in economics, with some economists seeing a significant rise in inflation on the horizon and others expecting the most recent increase in consumer prices to be a temporary phenomenon. The answer has significant implications for the conduct of monetary policy in Canada and therefore the trajectory of Canadian mortgage rates.

Since the implementation of inflation targeting in Canada, Canadian inflation expectations are well-anchored to the Bank of Canada’s 2 per cent target. Bond market measures of inflation expectations have come up slightly after a significant decline during the pandemic. Other survey measures of inflation expectations show that Canadians generally expect higher inflation five years from now, but one-year ahead inflation expectations remain anchored.

While inflation expectations appear well-anchored, there may be some risk of higher inflation due to an overstimulated economy, especially in light of serious supply shortages in many sectors. Canadian economic growth is forecast well above its roughly 1.8 per cent longrun trend rate. Driven by pent-up demand and aided by significant fiscal and monetary stimulus, real GDP is forecast to grow about 6 per cent this year and 4 per cent next year. That said, the injury to the Canadian economy from COVID-19 was severe, with output falling approximately close to 15 per cent. That means that even with very strong economic growth, the Canadian output gap6 is estimated to close in 2022 and sustain at a slightly positive level thereafter that is consistent with 2 per cent inflation. While a valid concern, sustainably higher inflation would have to involve economic growth that is well beyond the economy's productive capacity and beyond what is currently expected by policymakers.

Finally, higher inflation could arise due to cost-push shocks from sharp increases in wages or raw materials. For some raw materials, recent year-over-year increases are mainly the product of so-called “base-year” effects as normal prices today are compared with prices that were driven to historically abnormal levels during the pandemic. Such is the case with oil prices, which briefly turned negative during the pandemic and have since recovered. Other products, most notably lumber prices, have skyrocketed due to shortages, the origins of which trace back to well before the pandemic but were exacerbated by COVID-19. As these prices rise, so does the cost of production, which could be passed on to consumers through higher prices.

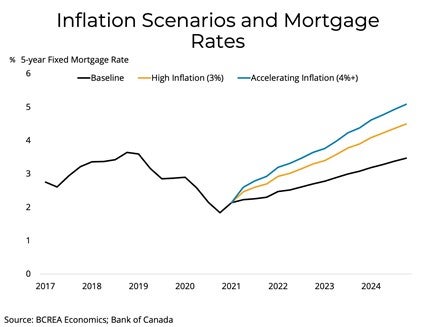

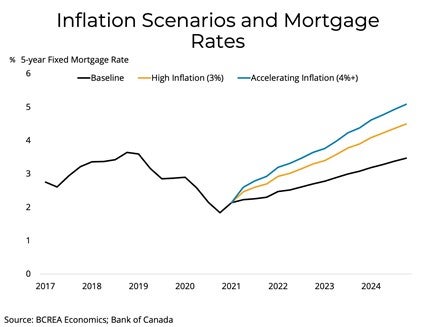

Finally, higher inflation could arise due to cost-push shocks from sharp increases in wages or raw materials. For some raw materials, recent year-over-year increases are mainly the product of so-called “base-year” effects as normal prices today are compared with prices that were driven to historically abnormal levels during the pandemic. Such is the case with oil prices, which briefly turned negative during the pandemic and have since recovered. Other products, most notably lumber prices, have skyrocketed due to shortages, the origins of which trace back to well before the pandemic but were exacerbated by COVID-19. As these prices rise, so does the cost of production, which could be passed on to consumers through higher prices. Indeed, the most recent inflation data, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), showed a significant uptick of inflation to its highest level in a decade at 3.5 per cent, though largely due to a jump in energy prices compared to the early months of the pandemic. The prevailing majority view on inflation seems to be tilted toward recent increases being a temporary phenomenon that should settle over the next year. If so, we should see an orderly unwinding of monetary stimulus with a gradual upward trajectory for mortgage rates, settling under 4 per cent in 2024.

For mortgage rates to rise meaningfully higher than 4 per cent, inflation would have to be sustained north of 3 per cent, or expectations of future inflation would have to become unmoored, leading the Bank of Canada to raise rates more aggressively than currently expected. While such a scenario is unlikely, it remains a risk given current elevated uncertainty.

Source - BCREA